|

An intrinsically motivated agent

|

How is it possible to discover what can be controlled from images ?

|

This blog post is accompanied with a colab notebook

Despite recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, machine learning agents remain limited to tasks predefined by human engineers. The autonomous and simultaneous discovery and learning of many-tasks in an open world remains very challenging for reinforcement learning algorithms. In this blog post we explore recent advances in developmental learning to tackle the problems of autonomous exploration and learning.

Consider a robot like the one depicted on the first picture. In this environment it can do many things: it can move its arms around, use its arms to play with the joysticks, move the ball in the arena using the joysticks. Imagine that we want to teach this robot how to move the ball to various locations. We could craft a reward function that rewards the agent for putting the ball at a given location, and launch our favorite deep RL algorithm. Without going into details, this popular approach has several drawbacks:

- the algorithm would require a lot of trials before sampling an action which might move the ball

- the robot would only learn how to move the ball but not how to move its arms to many locations, and even less how to move other objects that are unrelated to the ball

- we would need to specifically craft a reward for this task (this may be hard in itself (Christiano et al.))

Now imagine that we want the agent to learn all these tasks, i.e. learn to control various objects, without any supervision or reward. One strategy inspired by infants’ development that was shown to be efficient in this case consists in modeling the robot as a curiosity driven agent that wants to explore the world, by autonomously generating and selecting goals that provide maximal learning progress (Forestier et al.). Concretely, the robot sets for itself goals that it then tries to achieve, in an episodic fashion. For example one goal could be to put its arm at a specific place, or achieve a specific trajectory, or to try and move the ball to a certain location. Using this strategy the robot will soon realize that some goals are easier to reach than others, focusing on them and progressively shifting to learn more and more complex goals and associated policies. At the same time, it will also avoid spending too much time exploring goals that are either trivial or impossible to learn (e.g. distractor objects that move independently of the actions of the robot).

This idealized situation is fine, but what if we want our robot to learn all these skills using only raw pixels from a camera? What would a goal look like in this case? The robot could sample goals uniformly in the pixel space. This is clearly a poor strategy, as it amounts to sample noise which is by definition not reproducible. The robot could also sample images from a database of observed situations, and try to reproduce them. It could then try to compare the results of its actions with the goals. However, computing distances in the pixel space is a bad idea, as noise and changes in the scene (due to distractors for example) could put large distances between perceptually equivalent scenes.

From our perspective, we know that the world is structured and made of independent entities, with distinct properties. There are much fewer entities than the number of pixels in an image. As such it makes more sense to set goals for the entities rather than for the pixels that represent them. As humans we are very good at detecting those entities in an image and that’s what allows us to be efficient even in an unseen environment.

Coming back to our robot, is it possible for it to discover and learn to represent the entities in the environment from raw images? Can the robot use them to set goals that it can try to achieve? Will this lead to an efficient exploration of the environment? Can it discriminate between entities that can be controlled and those that cannot?

Those are the questions that we explored in two papers (Péré et al., ICLR 2018 and Laversanne-Finot et al. CoRL 2018). In particular, we show that:

- It is possible to leverage tools from the representation learning literature in order to extract features that can serve as goals for intrinsically motivated goal exploration algorithms.

- Using a representation of the environment as a goal space can provide performances as good as engineered features for exploration algorithms.

- Using disentangled representation is beneficial for exploration algorithms in the presence of distractors: using a disentangled representation as a goal space allows the agent to explore its environment more widely in a shorter amount of time.

- Curiosity driven exploration allows to extract high level controllable features of the environment when the representation is disentangled.

Environments

The experiments that we describe have been performed on variants of the Arm-Ball environment. In this environment a 7-joint robotic arm evolves in a scene containing a ball that can be grasped and moved around by the robotic arm. The agent perceives the scene as a 64 \times 64 pixels image. Simple as it may be, this environment is challenging since the action space is highly redundant. Random motor commands will most of the time produce the same dynamic: the arm moving around and the ball staying in the same position. Here we consider two variants of this environment: one where there is only the ball and one with an additional distractor: a ball that cannot be controlled and moves randomly across the scene. Examples of motor commands performed on these environments are presented on the figure above.

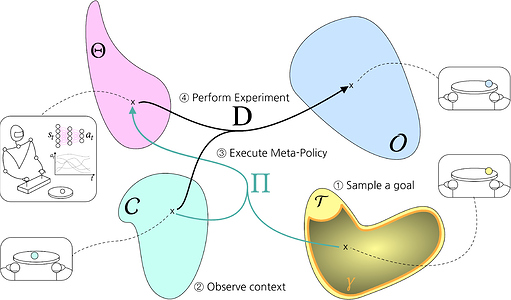

Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Process (IMGEPs)

A good exploration strategy for the agent when there is no reward signal is to set for itself goals and to try to reach them. This strategy, known as Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Processes (IMGEPs) (Forestier et al., Baranes et al.), is summarized in the figure above. For example, in this context, a goal could consist in trying to put the ball at a specific position (more generally, in the IMGEP framework, goals can be any target dynamical properties over entire trajectories). An important aspect of this approach is that the agent needs to have a goal space to sample those goals.

Up to now the Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Process approach has only been applied in experiments where we have access hand-designed representations of the state of the system. Now, consider a problem where a robot has to move an object from the raw images that it gets from a camera. The images are naturally living in a high dimensional space. However, we know that the underlying state is low dimensional (the number of degrees of freedom of the object).

In this case, a natural idea is to learn a low dimensional state representation. Having a state representation is advantageous in many ways Lesort et al.: to overcome the curse of dimensionality, it is easier to understand and interpret from a human point of view and it might improve performance and learning speed in machine learning scenarios. Another advantage of using state representation is that a policy learned on a representation is often more robust to changes in the environment. For example, if we consider a typical transfer learning scenario where the relevant parameters of the problem are kept fixed (e.g. shape and size of the object) but some irrelevant parameters may have changed (e.g. the color of the object that must be grasped by the robot) a policy learned on the pixel space is bound to fail when transferred, whereas the representation may still capture the relevant parameters.

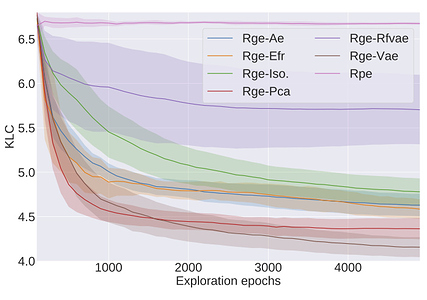

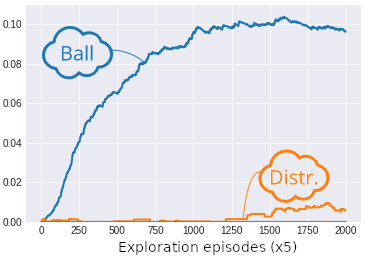

In a first paper (Péré et al.), we proposed to learn a representation of the scene using various unsupervised learning algorithms, such as Variational Auto-Encoders. The general idea consists in letting the agent observe another agent acting on the environment (enabling to observe a distribution of possible outcomes in that environment), and learn a compressed representation of these outcomes, called a latent space. The learned latent space can then be used as a goal space. In this case, instead of sampling as a goal the position of the ball at the end of the episode, the goal consists in reaching a certain point in the latent space (i.e. to obtain an observation at the end of the episode whose representation is as close as possible to the goal in the latent space). In this paper, it was shown that is is possible to use a wide range of representation algorithms to learn the goal space. Most of these algorithms perform almost as well as a true state representation. For instance the figure above shows that without any form of supervision or reward signal the agent is capable of learning how to place the ball in many distinct locations. On the contrary when the agent performs random motor commands (RPE) the diversity of outcomes is much smaller.

Modular IMGEPs

The results published in the first paper were obtained in environments containing always a single object. However, in many environments there is often more than one object. These objects can be very different and can be controlled with a varying degree of difficulty (e.g. moving a small object, hard to pick up vs moving a big ball across the environment). Or it can also happen that it is necessary to know how to use one object to use another one (e.g. using a fork to eat something). There can even be objects that are uncontrollable (e.g. moving randomly). As a result it seems natural to separate the exploration of different categories of objects. The intuitive idea is that an algorithm should start with controlling easy to learn objects before moving to more complex objects. It should also ignore objects that cannot be controlled (distractors). This is precisely what modular IMGEPs where designed for. The idea is that instead of sampling goals globally (i.e. target value for all dimensions characterizing the world and including all objects), the algorithm samples goals only as target values for particular dimensions of particular objects. For example, in the previously considered experiment the agent could decide to set a goal for the position of the joystick or for the position of the ball. By monitoring how well it performs for each task (the progress) the agent would discover that the ball is much harder to control than the joystick since it is necessary to master the joystick before moving the ball. By focusing on tasks (i.e. sampling goals for specific modules) for which the agent has a large learning progress the agent will always set for itself goals with the adequate difficulty. This approach leads to the formation of an automatic curriculum.

Ideally, in the case of goal spaces learned with a representation algorithm, if the representation is disentangled, then each latent variable corresponds to one factor of variation (Bengio). It is thus natural to see one, or a group, of latent variables as an independent module in which to set goals that could be explored by the agent. If the disentanglement properties of the representation are good, then it should in principle lead the agent to discover, through the representation, which objects can and which cannot be controlled. On the contrary, using an entangled representation will introduce spurious correlations between the action of the agent and the outcomes, which in turn will lead the agent to sample more frequently actions that in fact did not have any impact on the outcome.

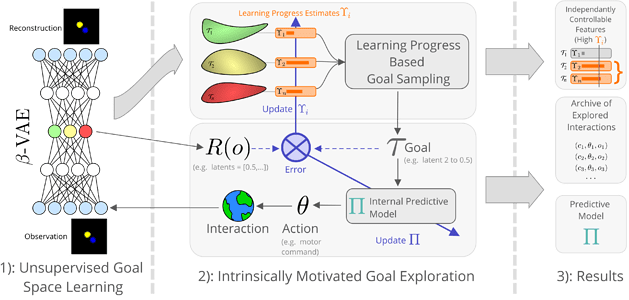

Following this idea, in a second paper (Laversanne-Finot et al.), we adopted the architecture in the above picture. The architecture is composed of a representation algorithm (in our case a VAE/\beta-VAE (Higgins et al.)) which learns a representation of the world. Using this representation we define modules by grouping some of the latent variables together. For example a module could be made of the first and second latent variables. A goal for this module would be to reach a position where the first and second latent variables have certain values. The idea behind this definition of modules is that if the modules are made of latent variables encoding for independent degrees of freedom/objects, then the algorithm should be able, by monitoring the progress, to understand which latent variables can or cannot be controlled. In other words, it will discover independently controllable features of the world.

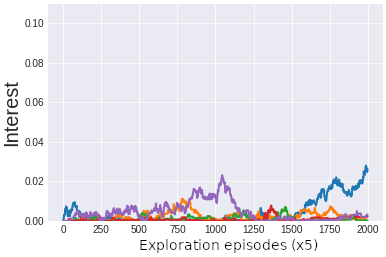

VAE, 5 modules

|

βVAE, 5 modules

|

βVAE, 10 modules

|

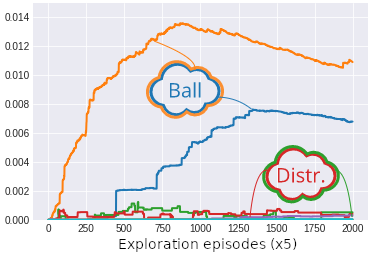

This is illustrated in the figure above. For example, when the goal space is disentangled and the modules are defined by groups of two latent variables, we see that the interest of the agent is high only for the module encoding for the ball position. On the other hand when the representation is entangled all the latent variables encode for the ball and distractor positions and thus the interest is low for all latent variables. Similar results are obtained if we define modules made of only one latent variable: when the goal space is disentangled the interest is high only for modules which encode the ball position, whereas when the representation is entangled all the modules have similar interest. The high interest is thus a marker that this latent variable is an independantly controllable feature of the environment.

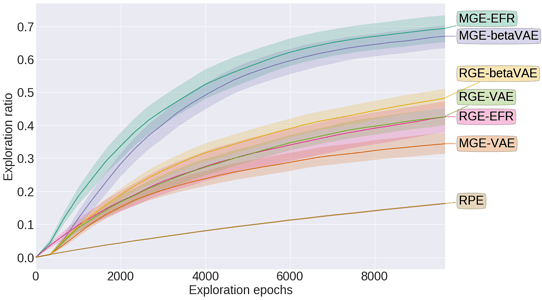

The fact that the algorithm is capable of extracting the controllable feature of the environments is reflected on its exploration performance. As seen on the figure below, modular goal exploration (MGE) algorithms with disentangled representations (\beta-VAE) explore much more than their entangled (VAE) counterparts, with performances similar to modular goal exploration with engineered features (EFR) (x and y positions of the ball and the distractor). We also see that in the presence of a distractor the performances of flat architecture (RGE) is negatively impacted.

Future work

In this series of works we studied how handcrafted goal spaces can be replaced by embeddings learnt from raw observations of images in IMGEPs. We have shown that, while entangled representations are a good baseline as goal spaces for IMGEPs, when the representation possesses good disentanglement properties, they can be leveraged by a curiosity-driven modular goal exploration architecture and lead to highly efficient exploration. In particular, this enables exploration performances as good as when using engineered features. In addition, the monitoring of learning progress enables the agent to discover which latent features can be controlled by its actions, and focus its exploration by setting goals in their corresponding subspace. This allows the agent to learn which are the controllable features of the environment.

An interesting line of work beyond using learning progress to discover controllable features during exploration, would be to re-use this knowledge to acquire more abstract representations and skills. For example, once we know which latent variables can be controlled, we can use a RL algorithm to learn to use them to acquire a specific skill in that environment.

Another interesting perspective would be to apply the ideas developed in these papers to real world robotic experiments. We are currently working on such a project. The setup that we are working on is very similar to the one presented throughout this blog post (see first picture): a robot can play with two joysticks. These two joysticks control the position of a robotic arm that can move a ball inside an arena. Currently the position of the ball and of the arm is extracted from the images using handcrafted features. Modular IMGEPs using those extracted features have been shown to be very efficient for exploration in this setup (Forestier et al.). The focus of our work is to remove this part and replace it with an embedding that would serve as a goal space.

Of course our approach is not the only possible one and the ideas developed in these papers may be applicable in other domains. In fact, similar ideas have been experimented in the context of Deep Reinforcement Learning. For example, it was suggested (Nair et al.) to rather train the RL algorithm in the embedding space obtained after training a Variational Auto Encoder (VAE) on images of the scene. Using this approach, it was shown that a robot can learn how to manipulate a simple object across a plane. However this paper did not study how the algorithm would perform in the presence of a distractor (an object that cannot be controlled by the robot but can move across the scene). In this case it is not clear that the RL algorithm would succeed since the embedding for two similar positions of the ball can vary wildly due to the distractor. See also (Bengio et al.) for another approach to discovering independently controllable features.

Code and notebook

References

- Curiosity Driven Exploration of Learned Disentangled Goal Spaces, Laversanne-Finot, A., Péré, A., & Oudeyer, P. Y., CoRL, 2018.

- Unsupervised Learning of Goal Spaces for Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration, Alexandre Péré, Sébastien Forestier, Olivier Sigaud, Pierre-Yves Oudeyer, ICLR, 2018.

- Hindsight Experience Replay, Marcin Andrychowicz, Filip Wolski, Alex Ray, Jonas Schneider, Rachel Fong, Peter Welinder, Bob McGrew, Josh Tobin, Pieter Abbeel, Wojciech Zaremba.

- Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences, Paul Christiano, Jan Leike, Tom B. Brown, Miljan Martic, Shane Legg, Dario Amodei.

- Early Visual Concept Learning with Unsupervised Deep Learning, Irina Higgins, Loic Matthey, Xavier Glorot, Arka Pal, Benigno Uria, Charles Blundell, Shakir Mohamed, Alexander Lerchner.

- Visual Reinforcement Learning with Imagined Goals, Ashvin Nair, Vitchyr Pong, Murtaza Dalal, Shikhar Bahl, Steven Lin, Sergey Levine.

- Learning Deep Architectures for AI, Yoshua Bengio.

- State Representation Learning for Control: An Overview, Timothée Lesort, Natalia Díaz-Rodríguez, Jean-François Goudou, David Filliat.

- Independently Controllable Features, Emmanuel Bengio, Valentin Thomas, Joelle Pineau, Doina Precup, Yoshua Bengio.

- Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Processes with Automatic Curriculum Learning, Sébastien Forestier, Yoan Mollard, Pierre-Yves Oudeyer.

- Active learning of inverse models with intrinsically motivated goal exploration in robots, Adrien Baranes, Pierre-Yves Oudeyer, Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 2013.

Contact

Email: adrien.laversanne-finot@inria.fr

Twitter of Flowers lab: @flowersINRIA